The story of the Enron scandal,

Accounting Adventurista-style

The Enron scandal was revealed in 2001 – at that time, it was a huge American energy company based in Texas. When the scandal blew up, the company’s stock price fell from US$90 per share to less than $1 in 2 years. In late 2001, it filed for bankruptcy – considered largest corporate bankruptcy in US history at that time.

So what actually happened?

Many things, actually. I will try to summarise the main accounting issues in an easy-to-understand way.

Complicated and confusing financial statements

The financial statements were complicated and confusing to its shareholders and analysts –they were intentionally presented in such a way to mislead. The overriding principle was: show a high income and net asset values, to ensure that shareholders were happy and to present a positive financial image.

Revenue recognition

Other than building and maintaining power facilities, the company also provided services such as wholesale trading and risk management.

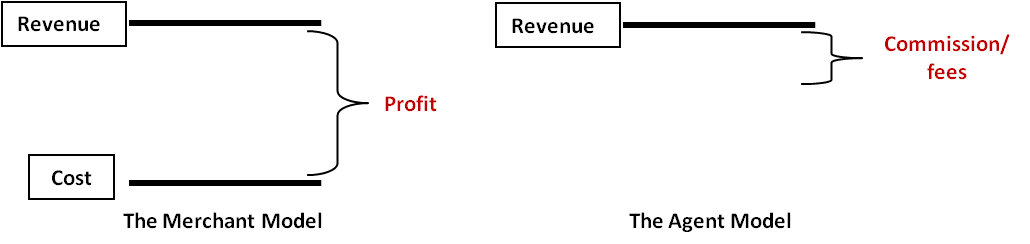

There are 2 approaches to this. When merchants buy and sell products, their revenue is the selling price of the products, and their cost is the cost of buying the product. This is allowed because when they buy the products, they take the risk of holding the products (e.g. theft, loss, accidents). When they sell, they also assume the risk of selling the products (e.g. fall in price, fall in demand). So we can say that merchants DESERVE to earn a higher profit in exchange for taking on such risks.

An agent (not a merchant) provides a service to the customer, but the risks involved are not as high. They are just middlemen who earn a commission on the sale – in other words, they take a cut from the transaction but they do not earn the entire profit of the said transaction.

So which approach did Enron choose? The former – in order to be able to record an inflated revenue and hence a higher profit on its books.

Mark-to-market accounting

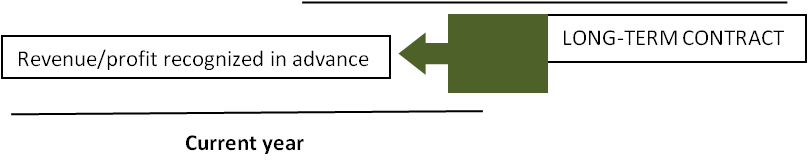

Conventionally, a company would recognize profit from the actual selling of gas (actual revenue minus actual costs). However, the company practised mark-to-market accounting on its long-term supply contracts.

This method allowed it to estimate and pre-recognise an amount of revenue from the contract. Often these contracts were not technically or financially viable and therefore the revenue/costs were not easily estimated. It is like taking advance credit for something that has not yet been done, and which may not even turn out well.

Mark-to-market accounting - a diagrammatic explanation

Special purpose entities (SPEs)

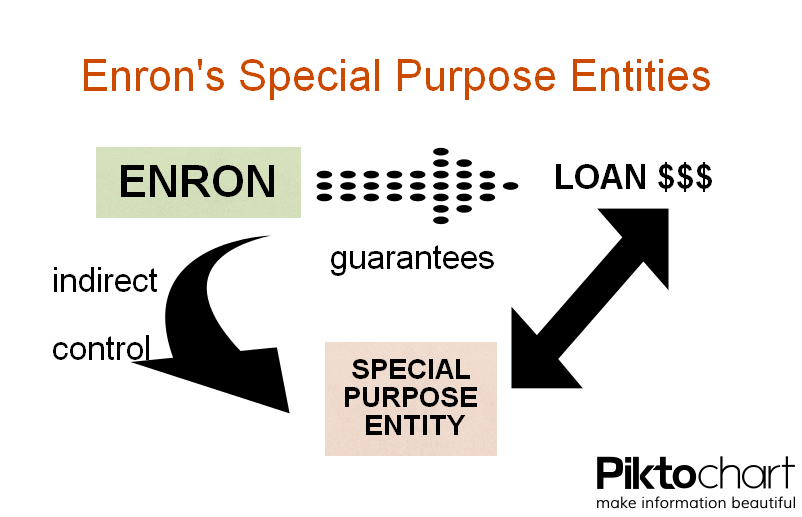

Another thing that the company did was to set up special purpose entities, which could be partnerships or companies. These entities were “shell” firms which were, on the surface, not linked to the company and were not officially part of the group. However, they were in fact closely linked – they were funded via (amongst other things) debt financing guaranteed by the company's shares and financial guarantees. In other words, the company used its own shares to guarantee the loans taken; it also guaranteed that it would repay the loans in case the entities were unable to pay. In effect, the company exerted indirect control over the SPEs. It was able to transfer liabilities and losses to these SPEs, thereby understating liabilities/overstating equity on its own balance sheet.

Other accounting issues

The company would capitalize, or treat as an asset, costs related to cancelled projects. It took the position that until there was an official letter stating that the projects were cancelled, the assets remained and were not written off (taken as losses). This practice was used for projects worth up to $200 million, thereby inflating the general asset level of the company.

Executive compensation

The company rewarded its employees based on their performance. However, the corporate culture was such that employees became obsessed with short-term earnings to maximize their bonuses. For example, they often entered into deals without considering their viability and sustainability. In terms of accounting, earnings results were recorded as soon as possible to maintain the company's share price.

As employees were also compensated using stock options (they were given the option to buy company stock/shares at a lower price compared to the rest of the market), they had a vested interest in boosting earnings to in turn boost the stock price – thereby boosting the value of their personal investment.

Financial audit

The auditor, Arthur Andersen, had different roles in Enron. Other than being the auditor, it also performed significant consulting work. Both roles represented a conflict of interest – it is like to performing a piece of work and then investigating that same piece of work – and led to it being accused of being less strict in its audits on Enron.

In the ensuing investigation, Andersen shredded tons of relevant documents and deleted nearly 30,000 e-mails and computer files – for that, it was charged guilty of obstruction of justice. The resulting damage to the Andersen reputation has been devastating.

Audit committee

Every large corporation has an audit committee, which usually meets periodically, such as once every quarter. Their role is to scrutinize and oversee financial matters. Enron's committee had accounting and finance expertise, but did not have the technical knowledge to question the rationale behind the company's special purpose entities. There were also suspicions of conflict of interest amongst the committee members.

Return to Accounting Scandals from Enron.

Return to The Accounting Adventurista Home.